Cabergoline

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (August 2023) |  |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dostinex, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | First-pass effect seen; absolute bioavailability unknown |

| Protein binding | Moderately bound (40–42%); concentration-independent |

| Metabolism | Liver, predominately via hydrolysis of the acylurea bond or the urea moiety |

| Elimination half-life | 63–69 hours (estimated) |

| Excretion | Urine (22%), feces (60%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.155.380 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

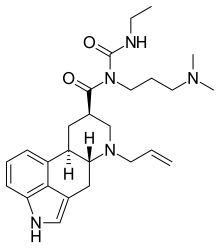

| Formula | C26H37N5O2 |

| Molar mass | 451.615 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Cabergoline, sold under the brand name Dostinex among others, is a dopaminergic medication used in the treatment of high prolactin levels, prolactinomas, Parkinson's disease, and for other indications.[2] It is taken by mouth.

Cabergoline is an ergot derivative and a potent dopamine D2 receptor agonist.[3]

Cabergoline was patented in 1980 and approved for medical use in 1993.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5]

Medical uses

[edit]- Lactation suppression

- Hyperprolactinemia[6]

- Adjunctive therapy of prolactin-producing pituitary gland tumors (prolactinomas);

- Monotherapy of Parkinson's disease in the early phase;

- Combination therapy, together with levodopa and a decarboxylase inhibitor such as carbidopa, in progressive-phase Parkinson's disease;

- In some countries also: ablactation and dysfunctions associated with hyperprolactinemia (amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, anovulation, nonpuerperal mastitis and galactorrhea);

- Treatment of uterine fibroids.[7][8]

- Adjunctive therapy of acromegaly, cabergoline has low efficacy in suppressing growth hormone levels and is highly efficient in suppressing hyperprolactinemia that is present in 20-30% of acromegaly cases; growth hormone and prolactin are similar structurally and have similar effects in many target tissues, therefore targeting prolactin may help symptoms when growth hormone secretion cannot be sufficiently controlled by other methods;

Cabergoline is frequently used as a first-line agent in the management of prolactinomas due to its higher affinity for D2 receptor sites, less severe side effects, and more convenient dosing schedule than the older bromocriptine, though in pregnancy bromocriptine is often still chosen since there is less data on safety in pregnancy for cabergoline.

Off-label

[edit]Cabergoline has at times been used as an adjunct to SSRI antidepressants as there is some evidence that it counteracts certain side effects of those drugs, such as reduced libido and anorgasmia. It also has been suggested that it has a possible recreational use in reducing or eliminating the male refractory period, thereby allowing men to experience multiple ejaculatory orgasms in rapid succession, and at least two scientific studies support those speculations.[9][10]: e28–e33 Additionally, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that prophylactic treatment with cabergoline reduces the incidence, but not the severity, of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), without compromising pregnancy outcomes, in females undergoing stimulated cycles of in vitro fertilization (IVF).[11] Also, a study on rats found that cabergoline reduces voluntary alcohol consumption, possibly by increasing GDNF expression in the ventral tegmental area.[12] It may be used in the treatment of restless legs syndrome.[citation needed]. Oral administration of cabergoline was faced with gastrointestinal problems which cause poor compliance in patients. One of the preferred solutions is to use non-oral dosage forms like suppositories. Vaginal suppositories have ease of use and could hinder gastrointestinal effects of cabergoline Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 31 (12): 101849. November 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101849. PMID 38028218. {{cite journal}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)</ref>.

Pregnancy and lactation

[edit]Relatively little is known about the effects of this medication during pregnancy and lactation. In some cases the related bromocriptine may be an alternative when pregnancy is expected.[citation needed]

- Pregnancy: available preliminary data indicates a somewhat increased rate of congenital abnormalities in patients who became pregnant while treated with cabergoline.[citation needed]. However, one study concluded that "foetal exposure to cabergoline through early pregnancy does not induce any increase in the risk of miscarriage or foetal malformation."[13]

- Lactation: In rats cabergoline was found in the maternal milk. Since it is not known if this effect also occurs in humans, breastfeeding is usually not recommended if/when treatment with cabergoline is necessary.

- Lactation suppression: In some countries cabergoline (Dostinex) is sometimes used as a lactation suppressant. It is also used in veterinary medicine to treat false pregnancy in dogs.

Contraindications

[edit]- Hypersensitivity to ergot derivatives

- Pediatric patients (no clinical experience)

- Severely impaired liver function or cholestasis

- Concomitant use with drugs metabolized mainly by CYP450 enzymes such as erythromycin and ketoconazole, because increased plasma levels of cabergoline may result (although cabergoline undergoes minimal CYP450 metabolism).

- Cautions: severe cardiovascular disease, Raynaud's disease, gastroduodenal ulcers, active gastrointestinal bleeding, hypotension.

Side effects

[edit]Side effects are mostly dose dependent. Much more severe side effects are reported for treatment of Parkinson's disease and (off-label treatment) for restless leg syndrome which both typically require very high doses. The side effects are considered mild when used for treatment of hyperprolactinemia and other endocrine disorders or gynecologic indications where the typical dose is one hundredth to one tenth that for Parkinson's disease.[citation needed]

Cabergoline requires slow dose titration (2–4 weeks for hyperprolactinemia, often much longer for other conditions) to minimize side effects. The extremely long bioavailability of the medication may complicate dosing regimens during titration and require particular precautions.

Cabergoline is considered the best tolerable option for hyperprolactinemia treatment although the newer and less tested quinagolide may offer similarly favourable side effect profile with quicker titration times.

Approximately 200 patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson's disease participated in a clinical study of cabergoline monotherapy.[14] Seventy-six (76) percent reported at least one side effect. These side effects were chiefly mild or moderate:

- GI tract: Side effects were extremely frequent. Fifty-three percent of patients reported side effects. Very frequent: Nausea (30%), constipation (22%), and dry mouth (10%). Frequent: Gastric irritation (7%), vomiting (5%), and dyspepsia (2%).

- Psychiatric disturbances and central nervous system (CNS): Altogether 51 percent of patients were affected. Very frequent: Sleep disturbances (somnolence 18%, insomnia 11%), vertigo (27%), and depression (13%). Frequent: dyskinesia (4%) and hallucinations (4%).

- Cardiovascular: Approximately 30 percent of patients experienced side effects. Most frequent were hypotension (10%), peripheral edema (14%) and non-specific edema (2%). Arrhythmias were encountered in 4.8%, palpitations in 4.3%, and angina pectoris in 1.4%.

In a combination study with 2,000 patients also treated with levodopa, the incidence and severity of side effects was comparable to monotherapy. Encountered side effects required a termination of cabergoline treatment in 15% of patients. Additional side effects were infrequent cases of hematological side effects, and an occasional increase in liver enzymes or serum creatinine without signs or symptoms.

As with other ergot derivatives, pleuritis, exudative pleura disease, pleura fibrosis, lung fibrosis, and pericarditis are seen. These side effects are noted in less than 2% of patients. They require immediate termination of treatment. Clinical improvement and normalization of X-ray findings are normally seen soon after cabergoline withdrawal. It appears that the dose typically used for treatment of hyperprolactinemia is too low to cause this type of side effects.

Valvular heart disease

[edit]In two studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine on January 4, 2007, cabergoline was implicated along with pergolide in causing valvular heart disease.[15][16] As a result of this, the FDA removed pergolide from the U.S. market on March 29, 2007.[17] Since cabergoline is not approved in the U.S. for Parkinson's Disease, but for hyperprolactinemia, the drug remains on the market. The lower doses required for treatment of hyperprolactinemia have been found to be not associated with clinically significant valvular heart disease or cardiac valve regurgitation.[18][19]

Interactions

[edit]No interactions were noted with levodopa or selegiline. The drug should not be combined with other ergot derivatives. Dopamine antagonists such as antipsychotics and metoclopramide counteract some effects of cabergoline. The use of antihypertensive drugs should be intensively monitored because excessive hypotension may result from the combination.

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Site | Affinity (Ki [nM]) |

Efficacy (Emax [%]) |

Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 214–32,000 | ? | ? |

| D2S | 0.5–0.62 | 102 | Full agonist |

| D2L | 0.95 | 75 | Partial agonist |

| D3 | 0.80–1.0 | 86 | Partial agonist |

| D4 | 56 | 49 | Partial agonist |

| D5 | 22 | ? | ? |

| 5-HT1A | 1.9–20 | 93 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT1B | 479 | 102 | Full agonist |

| 5-HT1D | 8.7 | 68 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT2A | 4.6–6.2 | 94 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT2B | 1.2–9.4 | 123 | Full agonist |

| 5-HT2C | 5.8–692 | 96 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 | – | – |

| 5-HT4 | 3,000 | ? | ? |

| 5-HT6 | 1,300 | ? | ? |

| 5-HT7 | 2.5 | ? | Antagonist |

| α1A | 288–>10,000 | 0 | Silent antagonist |

| α1B | 60–1,000 | ? | ? |

| α1D | 166 | ? | ? |

| α2A | 12–132 | 0 | Silent antagonist |

| α2B | 17–72 | 0 | Silent antagonist |

| α2C | 22–364 | 0 | Silent antagonist |

| α2D | 3.6 | ? | ? |

| H1 | 1,380 | ? | ? |

| M1 | >10,000 | – | – |

| SERT | >10,000 | – | – |

| Notes: All sites are human except α2D-adrenergic, which is rat (no human counterpart).[20] Negligible affinity (>10,000 nM) for various other receptors (β1- and β2-adrenergic, adenosine, GABA, glutamate, glycine, nicotinic acetylcholine, opioid, prostanoid).[21] Sources: [20][22][23][21][24] | |||

Cabergoline is a long-acting dopamine D2 receptor agonist. In-vitro rat studies show a direct inhibitory effect of cabergoline on the prolactin secretion in the lactotroph cells of the pituitary gland and cabergoline decreases serum prolactin levels in reserpinized rats.[citation needed] Although cabergoline is commonly described principally as a D2 receptor agonist, it also possesses significant affinity for the dopamine D3, and D4, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C, and α2-adrenergic receptors, as well as moderate/low affinity for the dopamine D1, serotonin 5-HT7, and α1-adrenergic receptors.[20][21][25] Cabergoline functions as an partial or full agonist at all of these receptors except for the 5-HT7, α1-adrenergic, and α2-adrenergic receptors, where it acts as an antagonist.[22][23][21] Cabergoline has been associated with cardiac valvulopathy due to activation of 5-HT2B receptors.[26]

Ergot derivatives like cabergoline have been described as non-hallucinogenic in spite of acting as serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists.[27]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Following a single oral dose, resorption of cabergoline from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is highly variable, typically occurring within 0.5 to 4 hours. Ingestion with food does not alter its absorption rate. Human bioavailability has not been determined since the drug is intended for oral use only. In mice and rats the absolute bioavailability has been determined to be 30 and 63 percent, respectively. Cabergoline is rapidly and extensively metabolized in the liver and excreted in bile and to a lesser extent in urine. All metabolites are less active than the parental drug or inactive altogether. The human elimination half-life is estimated to be 63 to 68 hours in patients with Parkinson's disease and 79 to 115 hours in patients with pituitary tumors. Average elimination half-life is 80 hours. The metabolism of Cabergoline is mediated by unidentified enzymes via a hepatic route and mainly consists of hydrolysis and oxidation by the alkylurea group and oxidation at the alkene.[28][29]

History

[edit]Cabergoline was first synthesized by scientists working for the Italian drug company Farmitalia-Carlo Erba in Milan who were experimenting with semisynthetic derivatives of the ergot alkaloids, and a patent application was filed in 1980.[30][31][32] The first publication was a scientific abstract at the Society for Neuroscience meeting in 1991.[33][34]

Farmitalia-Carlo Erba was acquired by Pharmacia in 1993,[35] which in turn was acquired by Pfizer in 2003.[36]

Cabergoline was first marketed in The Netherlands as Dostinex in 1992.[30] The drug was approved by the FDA on December 23, 1996.[37] It went generic in late 2005 following US patent expiration.[38]

Society and culture

[edit]Brand names

[edit]Brand names of cabergoline include Cabaser, Dostinex, Galastop (veterinary), and Kelactin (veterinary), among others.[39]

Research

[edit]Cabergoline was studied in one person with Cushing's disease, to lower adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels and cause regression of ACTH-producing pituitary adenomas.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ "Carbelin (Nova Pharmaceuticals Australasia Pty Ltd)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 13 September 2024. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Cabergoline: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2023-10-22.

- ^ Elks J, Ganellin CR (1990). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 204–.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 533. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ UK electronic Medicines Compendium Dostinex Tablets Last Updated on eMC Dec 23, 2013

- ^ Sayyah-Melli M, Tehrani-Gadim S, Dastranj-Tabrizi A, Gatrehsamani F, Morteza G, Ouladesahebmadarek E, et al. (August 2009). "Comparison of the effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and dopamine receptor agonist on uterine myoma growth. Histologic, sonographic, and intra-operative changes". Saudi Medical Journal. 30 (8): 1024–1033. PMID 19668882.

- ^ Sankaran S, Manyonda IT (August 2008). "Medical management of fibroids". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 22 (4): 655–676. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.03.001. PMID 18468953. http://www.britishfibroidtrust.org.uk/journals/bft_Sankaran.pdf

- ^ Krüger TH, Haake P, Haverkamp J, Krämer M, Exton MS, Saller B, et al. (December 2003). "Effects of acute prolactin manipulation on sexual drive and function in males". The Journal of Endocrinology. 179 (3): 357–365. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.484.4005. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1790357. PMID 14656205.

- ^ Hollander AB, Pastuszak AW, Hsieh TC, Johnson WG, Scovell JM, Mai CK, Lipshultz LI (March 2016). "Cabergoline in the Treatment of Male Orgasmic Disorder-A Retrospective Pilot Analysis". Sexual Medicine. 4 (1): e28–e33. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2015.09.001. PMC 4822480. PMID 26944776.

- ^ Youssef MA, van Wely M, Hassan MA, Al-Inany HG, Mochtar M, Khattab S, van der Veen F (March 2010). "Can dopamine agonists reduce the incidence and severity of OHSS in IVF/ICSI treatment cycles? A systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (5): 459–466. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq006. PMID 20354100.

- ^ Carnicella S, Ahmadiantehrani S, He DY, Nielsen CK, Bartlett SE, Janak PH, Ron D (July 2009). "Cabergoline decreases alcohol drinking and seeking behaviors via glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor". Biological Psychiatry. 66 (2): 146–153. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.022. PMC 2895406. PMID 19232578.

- ^ Colao A, Abs R, Bárcena DG, Chanson P, Paulus W, Kleinberg DL (January 2008). "Pregnancy outcomes following cabergoline treatment: extended results from a 12-year observational study". Clinical Endocrinology. 68 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03000.x. PMID 17760883. S2CID 38408935.

- ^ Rinne UK, Bracco F, Chouza C, Dupont E, Gershanik O, Marti Masso JF, et al. (February 1997). "Cabergoline in the treatment of early Parkinson's disease: results of the first year of treatment in a double-blind comparison of cabergoline and levodopa. The PKDS009 Collaborative Study Group". Neurology. 48 (2): 363–368. doi:10.1212/WNL.48.2.363. PMID 9040722. S2CID 34955541.

- ^ Schade R, Andersohn F, Suissa S, Haverkamp W, Garbe E (January 2007). "Dopamine agonists and the risk of cardiac-valve regurgitation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062222. PMID 17202453.

- ^ Zanettini R, Antonini A, Gatto G, Gentile R, Tesei S, Pezzoli G (January 2007). "Valvular heart disease and the use of dopamine agonists for Parkinson's disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054830. PMID 17202454.

- ^ "Food and Drug Administration Public Health Advisory". Food and Drug Administration. 2007-03-29. Archived from the original on 2007-04-08. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ Bogazzi F, Buralli S, Manetti L, Raffaelli V, Cigni T, Lombardi M, et al. (December 2008). "Treatment with low doses of cabergoline is not associated with increased prevalence of cardiac valve regurgitation in patients with hyperprolactinaemia". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 62 (12): 1864–1869. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01779.x. PMID 18462372. S2CID 7822137.

- ^ Wakil A, Rigby AS, Clark AL, Kallvikbacka-Bennett A, Atkin SL (October 2008). "Low dose cabergoline for hyperprolactinaemia is not associated with clinically significant valvular heart disease". European Journal of Endocrinology. 159 (4): R11–R14. doi:10.1530/EJE-08-0365. PMID 18625690.

- ^ a b c Millan MJ, Maiofiss L, Cussac D, Audinot V, Boutin JA, Newman-Tancredi A (November 2002). "Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 303 (2): 791–804. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.039867. PMID 12388666. S2CID 6200455.

- ^ a b c d Sharif NA, McLaughlin MA, Kelly CR, Katoli P, Drace C, Husain S, et al. (March 2009). "Cabergoline: Pharmacology, ocular hypotensive studies in multiple species, and aqueous humor dynamic modulation in the Cynomolgus monkey eyes". Experimental Eye Research. 88 (3): 386–397. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.003. PMID 18992242.

- ^ a b Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D, Audinot V, Nicolas JP, De Ceuninck F, Boutin JA, Millan MJ (November 2002). "Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. II. Agonist and antagonist properties at subtypes of dopamine D(2)-like receptor and alpha(1)/alpha(2)-adrenoceptor". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 303 (2): 805–814. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.039875. PMID 12388667. S2CID 35238120.

- ^ a b Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D, Quentric Y, Touzard M, Verrièle L, Carpentier N, Millan MJ (November 2002). "Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. III. Agonist and antagonist properties at serotonin, 5-HT(1) and 5-HT(2), receptor subtypes". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 303 (2): 815–822. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.039883. PMID 12388668. S2CID 19260572.

- ^ "PDSP Database - UNC". pdsp.unc.edu. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health. PDSD Ki Database (Internet) [cited 2013 Jul 24]. ChapelHill (NC): University of North Carolina. 1998-2013. Available from: "PDSP Database - UNC". Archived from the original on 2013-11-08. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- ^ Cavero I, Guillon JM (2014). "Safety Pharmacology assessment of drugs with biased 5-HT(2B) receptor agonism mediating cardiac valvulopathy". Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 69 (2): 150–161. doi:10.1016/j.vascn.2013.12.004. PMID 24361689.

- ^ Gumpper RH, Roth BL (January 2024). "Psychedelics: preclinical insights provide directions for future research". Neuropsychopharmacology. 49 (1): 119–127. doi:10.1038/s41386-023-01567-7. PMC 10700551. PMID 36932180.

- ^ https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020664s011lbl.pdf

- ^ https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-degradation-pathway-of-cabergoline_fig4_334374904

- ^ a b Council regulation (EEC) no 1768/92 in the matter of Application No SPC/GB94/012 for a Supplementary Protection Certificate in the name of Farmitalia Carlo Erba S. r. l.

- ^ Espace record: GB 202074566

- ^ US Patent 4526892 - Dimethylaminoalkyl-3-(ergoline-8'.beta.carbonyl)-ureas

- ^ Fariello RG (1998). "Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic features of cabergoline. Rationale for use in Parkinson's disease". Drugs. 55 (Suppl 1): 10–16. doi:10.2165/00003495-199855001-00002. PMID 9483165. S2CID 46973281.

- ^ Carfagna N, Caccia C, Buonamici M, Cervini MA, Cavanus S, Fornaretto MG, Damiani D, Fariello RG (1991). "Biochemical and pharmacological studies on cabergoline, a new putative antiparkinsonian drug". Soc Neurosci Abs. 17: 1075.

- ^ Staff. News: Farmitalia bought by Kabi Pharmacia[permanent dead link]. Ann Oncol (1993) 4 (5): 345.

- ^ Staff, CNN/Money. April 16, 2003 It's official: Pfizer buys Pharmacia

- ^ FDA approval history

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products - ANDA 076310". www.accessdata.fda.gov. FDA.gov. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Cabergoline Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Archived from the original on 2015-12-30.

- ^ Miyoshi T, Otsuka F, Takeda M, Inagaki K, Suzuki J, Ogura T, et al. (December 2004). "Effect of cabergoline treatment on Cushing's disease caused by aberrant adrenocorticotropin-secreting macroadenoma". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 27 (11): 1055–1059. doi:10.1007/bf03345309. PMID 15754738. S2CID 6660262.

- 5-HT1A agonists

- 5-HT1D agonists

- 5-HT2A agonists

- 5-HT2B agonists

- 5-HT2C agonists

- 5-HT7 antagonists

- Allyl compounds

- Alpha-2 blockers

- D2-receptor agonists

- D3 receptor agonists

- D4 receptor agonists

- Dimethylamino compounds

- Dopamine receptor modulators

- Drugs developed by Pfizer

- Italian inventions

- Lysergamides

- Non-hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists

- Prolactin inhibitors

- Theriogenology

- Ureas

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- Cardiotoxins